Imagine a kind of Rencontres d’Arles but without the Roman ruins, the searing heat and the café terraces. Situated in the heart of England, Derby is a relatively small city where Format Festival set up its quarters ten years ago. Like in Arles, it is easy to wander from an exhibition space to another while discovering the city, its architecture and its museums.

The theme of this year’s festival, Evidence, alludes to the origins of photography, its function of recording reality. Despite for the most part having totally different approaches, all the artists shown here question the status of the photograph as proof. The selection being particularly abundant, I will focus on some of my favourite works.

The Pearson building, the first exhibition space that I visited, is a pretty derelict place, stuck between past utility and future developments. Its walls, where you can distinguish various coats of paint, act as a background for the photographs.

On the ground floor, my eyes were caught for a long moment by Marianne Bjørnmyr’s Shadows/Echoes which combines both texts and photographs. This work is the fruit of a two year trip around Iceland during which the artist took an interest in the rather widely held belief of the existence of elves and fairies. Apparently, 53% of Icelandic people believe in them. Framed like the photos around them, the texts enable the spectator to enter this magical universe. Thanks to the dialog between her and a so-called Jónsdottir Ragnhildúr, we learn that these little beings live under rocks, that they like humans to consult them before building roads or that they often appear at dawn or dusk. This conversation, with a form that evokes documentary, influences the spectator in his/her understanding of the photographs whose authors include Ragnhildúr, icelandic photography pioneer Magnus Olfasson and the artist herself. Stereoscopic views, plays of light and nebulous landscapes operate as proofs, while unveiling the enigmatic aspect of reality.

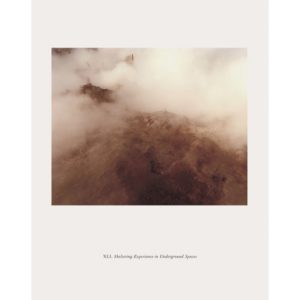

It is another aspect of reality that we discover on the floor above with David Fathi’s work. Under the title Anecdotal, the French artist offers a non-scientific study of the nuclear age. The series consists of various little stories or anecdotes about the nuclear weapon and tests conducted by different countries. The short texts are accompanied by images that mix film extracts, satellite imagery, often adjusted archives and photographs taken by David Fathi. Despite their diversity, these images share a singular unity and take us in a both absurd and frightening reality that recalls the atmosphere of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove. With the cold aesthetic of its photographs, David Fathi manages to evoke the imagery of the nuclear age and questions humans’ paradoxical fascination for the dreadful beauty of this weapon of mass destruction.

After the weary corridors of the Pearson Building, the modernity of the Quad gallery was a bit of a contrast! It is here, and amongst many others, that Cristina De Middel’s work is exhibited. I already knew this photographer from her series The Afronauts, a sort of poetic saga of the first and uncompleted Zambian space mission, which has been having a lot of success in the UK. At Format, she is showing a series called Jan Mayen, the name of a volcanic island located to the east of Greenland. Already discovered three centuries ago, this island was chosen by a group of European pseudoscientists to be the subject of a new expedition. Once arrived, they were compelled to turn back because their boat was too big to land. Their cinematographer convinced them to re-enact the disembarkment that never happened on a Icelandic beach. This is more or less how this completely extraordinary story is told by De Middel in her accompanying text. On the wall, black and white, sometimes colorized photographs illustrate this reconstituted adventure, with a great number of walking scenes in a steep landscape, pictures of explorer’s tools and wild animals. In front of this teeming selection, the spectator doesn’t know what to think as the line between the archival pictures and Cristina De Middel’s own photographs is so imperceptible. This illusionistic exercise is mastered so well that I still don’t know if this wall really included photographs from 1911. In the same vein as Joan Fontcuberta and with a very playful approach, Cristina De Middel incites us to always interrogate what we see.

St Werburgh church was the last destination of this busy day and I really enjoyed Phil Toledano’s series When I was six. At six years old, Phil Toledano lost his sister Claudia. She was nine. From the period following this drama, the artist only remembers a fascination for space and planets. An interest quite common from a little boy of this age but for Toledano, this seems to underline a desire of being somewhere else. After the death of his parents, he discovered a box in which his mother had kept a variety of objects that used to belong to Claudia: a strand of blond hair, a photo, a fan, a little baby checked dress. These belongings are photographed on a dark background, lit up by rays that seem to come from the window of a room during a winter afternoon. Other photographs, that convey the impression of interstellar landscapes, surround the still lives. A text, white on black, written in the first person, tells the disappearance, the mourning of the parents, his own mourning. Text and images are in perfect harmony. If there is evidence here, this is no doubt the overwhelming one of the passing of time.

Imaginez un genre de Rencontres d’Arles mais sans les ruines romaines, la chaleur écrasante et les terrasses de cafés. Située en plein cœur de l’Angleterre, Derby est une relativement petite ville où le festival Format a pris ses quartiers il y a de cela dix ans. Comme à Arles, il est aisé de voguer d’un lieu d’exposition à un autre tout en découvrant la ville, son architecture et ses musées.

Le thème de cette édition, Evidence (en français “indice” ou “preuve” mais aussi “évidence”), rappelle les origines de la photographie, sa fonction d’enregistrement du réel. Bien qu’ayant pour la plupart des démarches totalement différentes, les artistes exposés remettent tous en question ce statut de la photographie comme preuve. La sélection étant particulièrement foisonnante, je me concentrerai donc sur quelques-uns de mes coups de cœur.

Le Pearson building, premier lieu d’exposition que j’ai visité, est un bâtiment délabré, entre deux eaux, le passé et les développements futurs. Ses murs où l’on peut distinguer plusieurs couches de peinture, comme des témoins du fil du temps, font office d’arrière-plans aux travaux présentés.

Au rez-de-chaussée, mes yeux se sont arrêtés un long moment sur l’installation Shadows/Echoes (Ombres/Echos) mêlant textes et images de Marianne Bjørnmyr. Ce travail est le fruit d’un voyage de deux ans en Islande pendant lequel l’artiste s’est intéressée à la croyance largement répandue de l’existence des elfes et des fées. Apparemment, 53% des Islandais y croiraient. Encadrés comme les photos qui les entourent, les textes permettent au spectateur de pénétrer cet univers féerique. Grâce au dialogue entre l’artiste et une certaine Ragnhildúr Jónsdottir, on apprend entre autres que ces petits êtres vivent sous des rochers, qu’ils n’apprécient pas que les humains construisent des routes sans les consulter ou encore qu’ils apparaissent le plus souvent à l’aube ou au crépuscule. Cette conversation, dont la forme rappelle le documentaire, influence le spectateur dans sa compréhension des photographies présentées et dont les auteurs comprennent Ragnhildúr, le pionnier de la photographie islandaise Magnus Olfasson et l’artiste elle-même. Vues stéréoscopiques, jeux de lumière et paysages nébuleux font office de preuves, tout en dévoilant l’aspect énigmatique du réel.

C’est un autre aspect du réel que l’on découvre à l’étage avec le travail de David Fathi. Sous le titre Anecdotal (Anecdotique), l’artiste français propose une étude non-scientifique de l’âge nucléaire. La série est composée de plusieurs petites histoires ou anecdotes à propos de l’arme nucléaire et des tests menés par différents pays. Les textes courts sont accompagnés par des images mêlant extraits de films, images satellites, documents d’archives le plus souvent retravaillés et photographies prises par David Fathi. Malgré leur variété, ces images présentent une singulière unité, et nous transportent dans une réalité à la fois absurde et effrayante qui rappelle l’atmosphère du Docteur Folamour de Stanley Kubrick. A travers l’esthétique froide de ses photographies, David Fathi parvient à évoquer l’imagerie du nucléaire et questionne la fascination paradoxale des hommes pour l’effroyable beauté de cette arme de destruction massive.

Après les couloirs fatigués du Pearson Building, on peut dire que la modernité de la galerie Quad fait contraste ! C’est ici, et parmi beaucoup d’autres, que le travail de Cristina De Middel est exposé. Je connaissais déjà cette photographe dont la série The Afronautes, sorte de fresque poétique de la première mission spatiale inachevée de Zambie, a connu un franc succès au Royaume-Uni. A Format, elle présente une série intitulée Jan Mayen, du nom d’une île volcanique située à l’Est du Groenland. Découverte depuis déjà trois bons siècles, cette île fut choisie par un groupe de pseudo-scientifiques pour faire l’objet d’une nouvelle expédition. Arrivés à destination, ils furent contraints de rebrousser chemin car leur bateau était trop grand pour débarquer. Leur photographe, aussi déçu qu’eux, les persuada de recréer le débarquement qui n’eut jamais lieu sur une plage islandaise. C’est telle quelle que cette histoire, rocambolesque en tout point, est racontée par De Middel dans le texte d’accompagnement. Sur le mur, des photographies pour la plupart en noir et blanc, certaines colorisées, illustrent cette aventure reconstituée, à grand renfort de scènes de randonnées dans des espaces escarpés, d’images d’outils d’explorateur et d’animaux plus ou moins sauvages. Devant cette sélection foisonnante, le spectateur ne sait à quel saint se vouer tant la frontière entre les images d’archive et les photographies de Cristina De Middel est imperceptible. L’exercice d’illusionniste est si maitrisé que je ne sais toujours pas si ce mur comprenait vraiment des photographies datant de 1911. Dans la même veine que Joan Fontcuberta et à travers une démarche décidément ludique, Cristina De Middel nous encourage à toujours questionner ce que nous voyons.

L’église St Werburgh fut la dernière destination de cette journée bien remplie, avec un dernier coup de cœur pour la série When I was six (Quand j’avais six ans) de Phil Toledano. A six ans donc, Phil Toledano perdit sa sœur Claudia dans un incendie. Elle avait neuf ans. De la période qui suivit ce drame, l’artiste n’a souvenir que d’une fascination pour l’espace et les planètes. Un centre d’intérêt assez commun pour un petit garçon de cet âge-là mais qui, pour Toledano, semble sous-entendre un désir d’être ailleurs. A la suite du décès de ses parents, il découvrit une boîte dans laquelle sa mère avait gardé toutes sortes d’objets ayant appartenu à Claudia: une mèche de cheveux blond vénitien, une photo, un éventail, une petite robe de bébé à carreaux… Ces affaires sont photographiées sur un fond sombre, éclairées en biais par une lumière qui parait émaner de la fenêtre d’une chambre lors d’un après-midi d’hiver. D’autres photographies, qui semblent figurer des paysages interstellaires, entourent les natures mortes. Un texte, blanc sur noir, écrit à la première personne, raconte cette disparition, le deuil des parents, son deuil à lui. Texte et images sont en parfaite harmonie. S’il y a évidence ici, c’est sans doute celle, écrasante, du temps qui passe.